The Power of Iranian Cinema: Stories of Resilience, Resistance, and Humanity

I still remember the first time I watched A Separation (2011) about two years ago. I was aware of its acclaim, its Oscar victory, and the chorus of critical praise, yet nothing quite prepared me for the quiet intensity that unfolded on my TV screen on a quiet Tuesday evening. The film possessed a raw emotional honesty that felt almost intrusive in its intimacy. It eschewed grand gestures and manufactured climaxes, drawing its power instead from the intricate, suffocating moral dilemmas of its characters. When the credits rolled, I found myself sitting in a prolonged silence, overwhelmed by the narrative’s devastating weight. The experience offered an unfiltered portal into the complex fabric of Iranian society and, with startling clarity, reflected the universal struggles inherent in human relationships. That single film ignited a lasting fascination, drawing me into a film culture dedicated to weaving deeply personal stories with potent political undertones.

Cinema has always served as a formidable medium for storytelling, cultural expression, and societal introspection. While Hollywood and European cinema dominate global screens, Iranian cinema constitutes a unique and compelling force, one that merits a far wider audience. It operates as a vital gateway to understanding a nation of immense complexity, consistently presenting narratives that challenge and enrich the reductive geopolitical headlines dominating mainstream media. Through its poetic realism, its nuanced character studies, and its courageous social critique, Iranian cinema illuminates, questions, and connects, revealing the profound humanity that persists within, and often in spite of, formidable circumstances.

Source: A Separation (2011) Directed by Asghar Farhadi

A Legacy of Art and Resilience

Iranian cinema is widely regarded for its distinctive artistic tradition, one that masterfully blends unflinching realism with rich metaphor, weaving philosophical inquiry into the very fabric of ordinary life. This is a tradition built on intellectual and emotional integrity, a cinematic language that speaks with quiet power. Its celebrated legacy stretches back to the pioneering generation of the 1960s and 70s, a group of audacious artists including Abbas Kiarostami, Dariush Mehrjui, and the poet-filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad. Their groundbreaking work established a foundational principle for the industry: that compelling drama resides in the nuanced exploration of the human condition, often imbuing simple narratives with remarkable existential weight.

What makes this legacy even more extraordinary is the context of its creation. Iranian filmmakers have historically operated within a complex ecosystem of strict censorship and societal expectation. In response, they cultivated a sophisticated grammar of indirect expression, a cinematic language of immense subtlety. They learned to speak volumes through potent allegory, where a child's quest becomes a commentary on bureaucratic obstinance, and where the simple act of planting a tree can embody a nation's search for meaning. This ability to convey complex ideas through implication and visual poetry, rather than explicit dialogue, remains a defining characteristic and a testament to their creative ingenuity.

The global influence of this movement is perhaps best exemplified by the transcendent visual poetry of Abbas Kiarostami. His films, such as the Palme d'Or-winning Taste of Cherry (1997), a meditative journey on life and death, and the formally inventive Close-Up (1990), which reconstructs a true story with breathtaking humanity, embrace a radical minimalism. Kiarostami’s pioneering use of non-professional actors and his deliberate blurring of the lines between documentary and fiction were philosophical positions. This approach allowed him to dismantle the artifice of conventional storytelling, creating works that feel intensely immediate while grappling with universal truths about identity, truth, and our place in the world.

Simultaneously, Dariush Mehrjui forged a parallel path, igniting the Iranian New Wave with his seminal work, The Cow (1969). Where Kiarostami leaned towards the philosophical, Mehrjui wielded a sharp social realist lens. His films delivered piercing critiques of societal ills, economic disparity, and psychological despair, exploring themes of isolation, grief, and fractured identity with unvarnished honesty. Mehrjui’s courage in holding a mirror to his society, while working within and often against a restrictive system, paved the way for generations of filmmakers who understood that art could be a form of subtle, yet powerful, resistance.

This tradition of artistic resilience forms the very backbone of Iranian cinema's enduring identity. It is a tradition that continues to flourish, with directors like the humanistic Majid Majidi, whose films overflow with visual splendour and spiritual yearning, and the politically engaged Asghar Farhadi, a modern master of the moral thriller. Their work, and that of their contemporaries, ensures the industry remains a vital and dynamic force. These films function as living cultural documents, capturing the evolving spirit, anxieties, and enduring hopes of Iranian society. They stand as a powerful, ongoing testament to the idea that the most compelling art often emerges not in freedom from constraint, but in the courageous, creative dialogue with it.

A Voice for the Voiceless

A defining and powerful characteristic of Iranian cinema is its unwavering commitment to amplifying the voices of those on society's margins. Women, children, and the working class consistently occupy the narrative foreground, their stories portraying authentic struggles and perspectives that commercial filmmaking frequently overlooks. The works of internationally acclaimed directors such as Jafar Panahi and Asghar Farhadi masterfully illuminate deep-seated societal conflicts, systemic gender inequalities, and intricate moral dilemmas, all while navigating the complexities of Iran's socio-political landscape with remarkable dexterity.

Within a society where female voices have historically been constrained, Iranian cinema has provided a potent and resonant platform for their expression. Jafar Panahi’s The Circle (2000) presents a devastating, circular narrative that maps the suffocating restrictions imposed on women, while his film Offside (2006) uses a spirited, almost comedic premise to critique the absurdity of gender segregation. These films transcend their specific cultural context, offering a searing commentary on patriarchal structures that resonate with universal significance. They articulate a global language of resistance against systemic discrimination, giving form to struggles experienced by women in diverse societies.

Children, too, have become a central, poignant lens for social critique in Iranian storytelling. The international success of Majid Majidi’s Children of Heaven (1997) and Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon (1995) demonstrated how narratives of childhood innocence could expose harsh economic realities with disarming power. Through the eyes of a child searching for a lost pair of shoes or a single banknote, filmmakers articulate the weight of poverty and the quiet resilience of the young. This perspective allows them to deliver a critique that is simultaneously heartbreaking in its specificity and universally accessible in its emotional core.

Furthermore, Iranian cinema conducts an incisive exploration of class and economic disparity. Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning A Separation (2011) stands as a masterclass in this regard, meticulously dissecting how Iran’s class divisions fracture personal relationships and complicate moral choices. The film reveals how the most visceral human conflicts are frequently rooted in the immediate pressures of economic survival and social hierarchy, eclipsing abstract ideological disputes.

Operating under the constant shadow of censorship, these filmmakers have perfected an art of subtle subversion. Their work challenges authority not with overt manifestos, but through the empathetic, humanistic portrayal of ordinary lives. They provide a vital counter-narrative to reductive geopolitical portrayals, presenting Iran instead as a nation of poets, philosophers, and resilient individuals engaged in a universal struggle for dignity, justice, and a better life. In giving voice to the voiceless, they have secured their own enduring voice on the world stage.

Bridging the Gap Between Tradition and Modernity

A central, enduring preoccupation of Iranian cinema is its nuanced exploration of the tension between tradition and modernity. The screen becomes a vital arena where the societal shifts and internal conflicts of a nation in flux are dramatised with extraordinary sensitivity. This dialogue frequently manifests through the generational chasm separating conservative parents from their more liberal children, and through the complex struggles of women seeking autonomy within entrenched patriarchal structures. In this capacity, Iranian cinema functions as a dynamic mirror, capturing the evolving consciousness of its society.

The generational conflict forms a powerful narrative engine in many films. Younger characters are consistently portrayed questioning, challenging, or quietly resisting the weight of familial and cultural expectations. This theme finds potent expression in the work of directors like Dariush Mehrjui, whose film Leila (1997) dissects the pressures of marriage and motherhood imposed upon a young woman, and Tahmineh Milani, whose The Hidden Half (2001) uses a fraught political past to explore a woman's suppressed personal history. These stories articulate a quiet revolution, charting the difficult negotiation between individual desire and collective obligation.

Simultaneously, filmmakers scrutinise the accelerating forces of technology and globalisation. The pervasive influence of the internet, rapid urbanisation, and increased exposure to Western cultures present direct challenges to traditional norms, creating fissures within families and communities. The films of Asghar Farhadi masterfully capture this contemporary anxiety, presenting characters perpetually torn between a deep-seated duty to family and an increasingly compelling urge for personal freedom. His narratives unfold in a world where a smartphone can be as disruptive as a family secret, and where globalised aspirations clash with local realities.

Beyond social customs, Iranian cinema also engages courageously with the role of religious identity in a modernising world. Films like The Lizard (2004), a satirical comedy about a convict who impersonates a cleric, offer a daring and thought-provoking examination of how religious authority interacts with, and is sometimes undermined by, contemporary life. The film uses humour to pose serious questions about faith, hypocrisy, and the space for individual interpretation within a rigid system.

Collectively, these works present a compelling portrait of Iran as a society in a state of continuous, dynamic transition. They reveal a culture where ancient beliefs and modern ideals exist in a constant, often uneasy, dialogue. Iranian cinema resists simple resolutions, choosing instead to document the ongoing struggle, the moments of painful clash, and the occasional, unexpected harmonies that emerge from this profound national conversation.

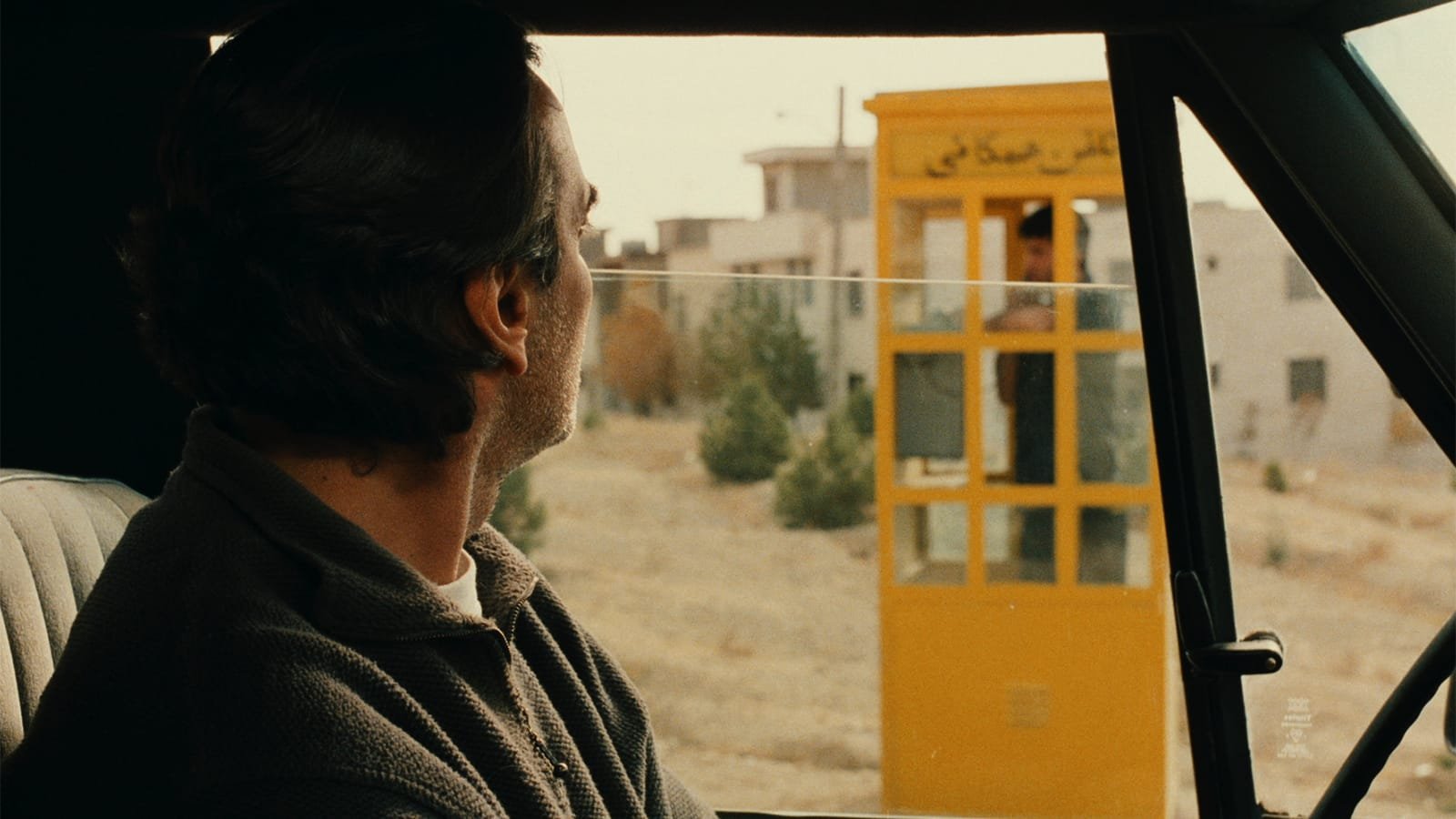

Source: Taste of Cherry (1997)

Breaking Censorship Through Creativity

The practice of filmmaking in Iran operates within a complex framework of state-imposed restrictions. Direct political criticism, the explicit depiction of certain social realities, and even the representation of intimacy between genders are subject to stringent control. Yet, in a remarkable demonstration of artistic resilience, these very constraints have catalysed a culture of profound ingenuity. Iranian directors have cultivated a sophisticated cinematic vocabulary rooted in metaphor, potent symbolism, and deliberate narrative ambiguity. This approach transforms the screen into a shared space of discovery, where meaning unfolds through the delicate interplay of suggestion and the audience's imagination.

The careers of filmmakers like Mohammad Rasoulof and Jafar Panahi stand as powerful testament to this defiant spirit. Both artists have endured severe personal consequences, including imprisonment and official bans from their profession. Despite this, they have persisted in creating bold, urgent works that directly challenge authoritarian structures and champion the necessity of artistic expression. Their unwavering commitment underscores a central truth about contemporary Iranian cinema: it frequently operates as a form of courageous cultural and political resistance, where the act of creation itself becomes a powerful statement against suppression.

This creative defiance manifests not only in content but in form. The restrictions have fostered a unique aesthetic of implication. A lingering shot on a closed door, the symbolic weight of a child's simple desire, or the fraught silence between two characters can carry more narrative and political charge than any explicit dialogue. This has compelled filmmakers to master the art of visual storytelling, where every frame is meticulously composed to suggest what cannot be directly shown. The result is a body of work that requires a engaged, discerning viewership, one that can read between the lines and appreciate the subtle artistry of speaking truth to power without uttering a forbidden word. In this way, Iranian cinema has transformed limitation into a distinctive artistic strength, proving that the most powerful messages are often those that are felt rather than heard.

Why Iranian Cinema Matters Now More Than Ever

In an era defined by misinformation, geopolitical polarisation, and reductive media narratives, Iranian cinema has emerged as an indispensable medium for human understanding. While international headlines frequently reduce Iran to a political adversary, its film industry offers a powerful, humanising counter-narrative. It showcases the richness of Iranian culture and illuminates the nuanced struggles, aspirations, and dreams of its people. Despite operating under immense pressure and systematic censorship, Iranian filmmakers persist in creating art that challenges authority, interrogates social norms, and amplifies the voices of the marginalised. Their work has become a global beacon of artistic resistance and human resilience.

The defiance embodied by filmmakers such as Jafar Panahi and Mohammad Rasoulof, who have faced imprisonment and official bans, represents the very heart of this cinematic tradition. Their continued artistic output, often produced under extraordinary duress, underscores that filmmaking in Iran constitutes both an artistic pursuit and a courageous act of political defiance. Whether through overtly political allegories or intimately personal dramas, their films articulate universal themes of freedom, justice, and dignity that resonate across cultures and borders.

What I find one of the most compelling strengths of Iranian cinema is its dedicated focus on those frequently silenced in public discourse. In a society where the perspectives of women, children, and the working class are often suppressed, filmmakers have transformed the camera into a tool of advocacy. Directors like Asghar Farhadi and Rakhshan Bani-E'temad craft intricate narratives that explore the delicate negotiations women must make within patriarchal structures. Farhadi’s A Separation (2011) masterfully dissects the intersections of gender, class, and morality, while Bani-E'temad’s Under the Skin of the City (2001) provides a raw, empathetic portrait of a working-class woman’s daily battles. These stories grant visibility and complexity to lives that are too often overlooked.

Amid escalating tensions between Iran and the West, this cinema provides a vital bridge for cross-cultural empathy. It counters monolithic media portrayals by revealing the country's intricate social fabric and shared human concerns. Films like Taste of Cherry (1997), with its philosophical meditation on life and death, and Children of Heaven (1997), with its poignant depiction of childhood innocence amid poverty, present stories that are simultaneously specific to the Iranian context and universal in their emotional appeal. They remind global audiences that Iran possesses a deep-rooted cultural history as a land of poets, philosophers, and ordinary people striving for a better life.

Furthermore, at a time of oversimplified political discourse, Iranian cinema offers a masterclass in navigating moral and social ambiguity. Filmmakers tackle complex issues — from gender inequality and economic disparity to the tension between tradition and modernity — with a refreshing subtlety. These films deliberately resist providing easy answers, instead inviting viewers to engage with the intricate dilemmas faced by their characters. This narrative approach challenges international audiences to move beyond preconceived notions and engage with the nuanced realities of Iranian society.

The growing international acclaim for Iranian directors, from Asghar Farhadi’s Academy Awards to the enduring global influence of Abbas Kiarostami, has cemented the art form’s significance on the world stage. This recognition facilitates a crucial cultural exchange, allowing wider audiences to access these vital stories through digital streaming platforms and international festivals. As political divisions harden, the empathetic window offered by Iranian cinema transforms from a cultural luxury into a critical instrument for fostering a more nuanced and compassionate global dialogue.

Source: The Circle (2000)

So Why Should You Watch Iranian Cinema?

The dominant narrative of Iran in Western media often presents a monolithic, politically charged portrait, one that consistently overshadows the nation's immense cultural heritage and the rich tapestry of its everyday human experiences. Iranian cinema offers a vital and compelling counter-narrative, serving as a direct portal for international audiences to discover a nation of poets, philosophers, and ordinary individuals whose lives are defined by universal struggles and aspirations. Films like Taste of Cherry (1997), with its philosophical contemplation of existence, and The Colour of Paradise (1999), with its poignant exploration of faith and perception, reveal an Iran that transcends geopolitical headlines—a land of breathtaking beauty, intricate complexity, and deep, abiding humanity.

In a contemporary media landscape increasingly characterised by homogenised storytelling, Iranian cinema stands as a powerful testament to film’s dual capacity as both a supreme art form and a crucial social instrument. It actively challenges entrenched perceptions, fosters a genuine and hard-won empathy, and provides an authentic glimpse into a culture frequently misunderstood by the outside world. To engage with Iranian cinema is to participate in one of the most significant and resilient cultural movements of our era — a tradition that often speaks in subtle, metaphorical whispers, yet whose humanistic messages resonate with a thunderous clarity across all borders.

For any viewer seeking a cinematic experience that transcends entertainment to enter the realms of high art and urgent social commentary, Iranian film presents an essential and deeply enriching journey. These stories function as a powerful reminder that beneath the surface of political and cultural divisions, the fundamental emotions of the human heart — the struggles for dignity, the yearning for love, the pursuit of justice — remain our shared global inheritance.

Approach Iranian cinema as a vital, enduring voice of resilience, quiet resistance, and profound revelation. Let these films be your guide to the real Iran, and in doing so, perhaps you will also discover something new about our interconnected world.

S xoxo

Written at Shebara Resort, Saudi Arabia

11th January 2025