Fashion as a Political Statement: How Clothing Became a Form of Protest

Fashion is often dismissed as the most frivolous of arts, a world of superficial trends. This is a profound misreading. Throughout history, what we have chosen to wear has been one of our most eloquent, dangerous, and accessible forms of political speech. Fashion has always functioned as a language, a sophisticated dialect of fabric and form that communicates long before any words are spoken. A person’s clothing articulates a preliminary statement, whispering or sometimes shouting their identity, their mood, their unspoken allegiances. To dress is to make a declaration; it is to align oneself with a specific tribe, a cultural movement, or a philosophical idea. Clothes are rarely, if ever, neutral. Even in their most restrained simplicity, they reflect a constellation of choices shaped by the immense forces of culture, history, and politics. The daily act of getting dressed, therefore, is the conscious act of positioning oneself within the intricate social landscape.

Beyond this personal declaration, fashion endures as one of our most potent and accessible tools of resistance. It is a silent yet thunderous form of defiance. A single, deliberate garment, worn at a precise cultural moment, possesses the capacity to ignite a revolution. A raised hemline can constitute an act of rebellion; a specific colour can shoulder the symbolic weight of an entire movement. The history of fashion is, in many ways, a parallel history of protest, one woven directly into textiles, stitched into the architecture of silhouettes, and embroidered with subversive meaning.

In a world where silence often equates to complicity, fashion offers a powerful alternative: a means to speak without uttering a word, to resist without raising a fist, to wear one’s beliefs quite literally on one’s sleeve. Consider the punk who meticulously tears and reassembles their clothes with safety pins, crafting a visual scream against conformity. Observe the feminist in a sharply tailored power suit, reclaiming sartorial codes of authority that were once a male prerogative. Witness the activist whose deliberate choice of mundane or symbolic attire becomes a powerful refusal to comply with oppressive norms.

Fashion, in these instances, remains an inherently political act. History has demonstrated, time and again, that the right outfit at the right moment can achieve far more than making a simple statement. It can galvanise a movement, crystallise a shared identity, and become an enduring emblem of change. From the suffragettes’ strategic use of white to the Black Panthers’ uniform of leather jackets and berets, clothing has consistently provided a visual vocabulary for revolution, proving that what we wear is never just about who we are, but about the world we wish to build.

Dior’s S/S 2017 by Maria Grazia Chiuri graphic t-shirts, which referenced a 2014 essay by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Personal as Political: Dressing for Dissent

We often imagine political statements as grand public gestures: organised marches, impassioned speeches, or lengthy manifestos. Yet sometimes, the most potent form of rebellion begins in the quiet of one’s own wardrobe. A black beret in 1960s America functioned as more than a simple hat; it served as a stark declaration of solidarity with the Black Panther Party. A pink pussyhat in 2017 was far more than a knitted accessory; it became a collective, visual roar against systemic misogyny. The suffragettes did not merely campaign for the vote; they did so deliberately draped in pristine white, transforming their clothing into a powerful visual shorthand for their cause.

This encapsulates the unique power of fashion as protest: it is immediate, unspoken, and utterly inescapable. It does not ask politely to be heard; it demands insistently to be seen. A slogan T-shirt, a coordinated sea of symbolic colour, an ensemble so deliberately subversive it cannot be ignored — these are all acts of dissent woven directly into fabric. Yet protest through fashion is not always loud. Sometimes, it is quiet yet no less radical, stitched into the everyday choices of individuals who refuse to conform. It manifests in the woman who walks into a boardroom in a sharply tailored suit, embodying an authority she was historically denied. It lives in the young man who paints his nails, fully aware of the social weight that simple act carries. It is the refusal to shrink, the rejection of imposed norms, the conscious decision to wear one's beliefs on one's sleeve.

To underestimate fashion is to fundamentally misunderstand the mechanics of power. Throughout history, clothing has been banned, criminalised, and meticulously regulated precisely because of its disruptive potential. Monarchs issued sumptuary laws dictating what fabrics and colours the lower classes could wear, ensuring social hierarchy was literally woven into privileged silks and velvets. Colonisers systematically erased indigenous dress, imposing Western attire as a blunt instrument of cultural control. Dictatorships have enforced sartorial uniformity, outlawing individual expression under the hollow guise of national unity. Even today, what people wear is policed, sometimes through legislation and often through social pressure, all underpinned by the same implicit understanding: fashion is a battleground for identity, a stage for performance, a megaphone for the marginalised.

At its most effective, protest fashion operates through sheer, undeniable visibility. It forces the world to look, to acknowledge, to react. When the women of the #MeToo movement arrived at the Golden Globes in an unspoken but unanimous wave of black gowns, the gesture transcended a simple colour choice. It was a funeral for silence, a sartorial uprising against an industry that had protected predators for decades. It served as a stark reminder that fashion, when wielded with collective intention, can carry the immense weight of an entire movement.

The case of Mahsa Amini, the young Iranian woman whose death in 2022 ignited a firestorm of protest, further illustrates this power. The simple, courageous act of removing one’s headscarf — seemingly mundane to outsiders — became an act of radical defiance, an unmasking of state-enforced oppression. When Iranian women stood in public spaces with their hair uncovered, they turned their own bodies into living battlegrounds for bodily autonomy. The world watched as headscarves were burned, as women cut their hair in a powerful ritual of mourning and rebellion. The very garment used to control them was transformed into the ultimate symbol of their resistance. In these moments, fashion was a weapon.

Crucially, protest fashion is not only reactive; it is also pre-emptive, a method of claiming space before permission is granted. It thrives in the calculated, glorious flamboyance of drag culture, a deliberate defiance of gender norms that long predates mainstream acceptance. It was present in the quietly revolutionary decision of women to wear trousers in the early 20th century, an act that seems unremarkable today only because of the fierce battles fought to normalise it.

Fashion may appear frivolous to those who choose not to look closely. But those in power have always recognised its significance; that is precisely why they have tried so hard to control it. And that is also why, throughout history, those who seek change have consistently turned to it as a means to fight back. Because clothing, in the end, is the message we choose to broadcast when words are insufficient, when doors are closed, and when silence is no longer an option.

The Fabric of Rebellion: Subversion Through Style

Protest fashion rarely operates with the blunt clarity of a slogan on a T-shirt. Often, its most potent forms move in the shadows, slipping past censors and societal expectations, their defiance woven into the very seams of a garment. This is the art of sartorial subversion: playing with the established codes of power and twisting them until they no longer serve their original architects.

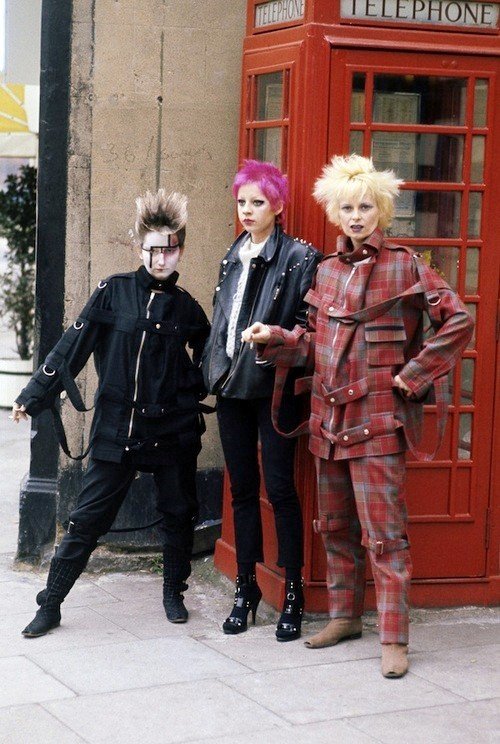

For example, the Mods of 1960s Britain, who appropriated the elegant attire of upper-class dandies — sharp Italian suits, immaculate parkas — and mounted them on roaring Vespas that tore through working-class streets. Their style was a brilliant cultural hijacking, transforming elitist fashion into a uniform for youthful rebellion that defied rigid class hierarchies. Similarly, Vivienne Westwood and the punk movement weaponised the discarded and the industrial. Torn fishnets, battered leather, and utilitarian safety pins were assembled into a visual manifesto that screamed chaos and anarchy directly into the face of a society obsessed with order and propriety. Further back, the Zoot Suit Riots of the 1940s saw Mexican-American youths adopt extravagantly oversized, flamboyant suits. These exaggerated silhouettes became powerful symbols of cultural pride and defiant visibility in a nation that actively sought to marginalise them.

1940-42 zoot suit © Museum Associates / LACMA

This practice of subversion through style is a game as old as power itself. During the French Revolution, the sans-culottes — literally “without breeches" — made a revolutionary statement by rejecting the aristocratic knee-breeches (culottes) in favour of the long trousers of the labouring class. What seems a mundane sartorial choice today was then a radical rejection of the monarchy's sartorial dominion, an insistence that fashion should not be the exclusive property of the ruling elite. Their clothing was a fabric declaration of allegiance to a new social order.

In the grey uniformity of Soviet Russia, blue jeans became a luminous symbol of forbidden Western decadence. The state’s ban on this quintessential capitalist fabric only amplified its desirability. Smuggling a pair of Levi's past the Iron Curtain was a deeply personal act of rebellion, a quiet but firm rejection of state-imposed conformity. The humble denim of the American worker became, paradoxically, a glamorous and dangerous emblem of individual freedom behind the Iron Curtain. The authorities’ attempts to repress it only strengthened its symbolic power.

Even in our contemporary landscape, clothing continues to function as a potent, if quieter, force of defiance. The recent phenomenon of “quiet luxury" presents a fascinating case. Superficially, this aesthetic — the rejection of logos and overt displays of wealth in favour of impeccable tailoring and exquisite, understated fabrics — appears to be the antithesis of protest. In reality, it represents rebellion in its most sophisticated and insidious form. The wealthy elite have recalibrated their signalling; they no longer need to “shout" their status. Instead, they “whisper" it through a cashmere coat cut with surgical precision, a fabric so rarefied it is legible only to those within the same exclusive circles. The absence of an overt statement becomes the most powerful statement of all.

In my opinion, however, this shift is fundamentally about control. Historically, wealth required ostentation to be validated, think of the gilded embroidery and lavish furs of monarchs. The modern elite have rewritten this contract. They now signal power not through volume but through impenetrable exclusivity. A discreet, unbranded Brunello Cucinelli sweater does not cry “I am rich" in the manner of a logo-emblazoned handbag. Instead, it murmurs, “I am so securely positioned that I have no need for your recognition." It is a rebellion against the very spectacle of mass consumerism, a refusal to participate in its gaudy theatre while still enjoying its most luxurious spoils.

Naturally, this particular form of subtle defiance is a privilege afforded only to a select few. The luxury of rebellion, whether loud or quiet, has always been distributed unequally. A hedge fund manager in an exquisitely cut, label-less suit is perceived as refined and authoritative. A teenager from a council estate in an oversized hoodie may be viewed with suspicion and prejudice. The same sartorial codes of restraint and anonymity are interpreted through the unforgiving lens of class and race.

This disparity reveals where the most courageous act of fashion rebellion truly resides: in the steadfast reclamation of one's own narrative. It is the refusal to be defined by the assumptions and biases of others, whether through glorious extravagance or deliberate minimalism. The fundamental act of choosing what to wear, and in doing so, asserting one's identity against the pressures to conform, remains a powerful political gesture. Ultimately, fashion is never merely about fabric. It is a complex and endless negotiation of perception, power, and the eternal human tension between fitting in and standing apart.

The Commodification of Protest: Who Gains, Who Loses?

One of fashion’s most formidable strengths as a tool for dissent simultaneously constitutes its most significant vulnerability: its inherent susceptibility to co-option. A style that begins as a potent act of subversion can be swiftly absorbed into the mainstream, systematically stripped of its radical origins and repackaged as a depoliticised aesthetic. The punk movement, which germinated as a raw, furious rejection of consumerist culture, now exists as a heavily commercialised trend available on high streets worldwide. The political urgency of its ripped shirts and anarchist symbols has been methodically dulled by mass production, its rebellious spirit sanitised and sold back to the very system it once sought to dismantle. This cycle of appropriation and neutralisation has befallen countless other movements. Countercultures that once derived their power from their opposition to the status quo frequently watch their symbols become mass-produced commodities, their messages diluted, their original, potent meanings buried beneath layers of commercial appeal.

But who truly benefits when radical fashion is commercialised? The answer rarely includes the marginalised communities who pioneered these movements. The individuals who originally wore protest fashion out of political necessity or defiant self-expression are often erased from the narrative the moment their aesthetic becomes financially marketable. Consider the Black and Latinx youth who forged the language of streetwear from limited resources and boundless creativity, the queer pioneers who courageously experimented with gender-fluid dressing long before it was a branded concept, or the indigenous communities whose sacred patterns and traditional textiles have been endlessly “reinterpreted" by luxury fashion houses. These originators almost never receive a meaningful share of the immense profits generated from their cultural and political innovations.

Meanwhile, the established fashion industry, with its insatiable appetite for novelty, profits enormously. It performs a kind of alchemical extraction, separating the visually compelling elements of a movement from their inconvenient political context. The industry then sells this hollowed-out aesthetic back to a mass audience, transforming symbols of resistance into mere signifiers of cool. This process is exploitative and actively de-fangs dissent. A slogan that once challenged power becomes a decorative print; a silhouette born from struggle becomes just another seasonal trend. The system, in a remarkable display of capitalist resilience, consumes its own opposition and sells the remains, leaving the original protesters both unrecognised and uncompensated while the machinery of fashion continues its relentless, profitable turn.

From Subversion to Product: The Lifecycle of Radical Fashion

A predictable, almost mechanical pattern governs how the fashion industry absorbs and neutralises resistance. This cycle begins at the social margins, where style is forged not from a desire to be fashionable, but from an urgent need for identity and survival. Consider working-class youths in 1970s London, transforming industrial safety pins and discarded leather jackets into the brutal poetry of punk rebellion. Or the drag artists in New York's ballroom scene, who crafted an entire visual lexicon of queerness from thrift-store finds and breathtaking ingenuity, creating visibility in a world determined to render them invisible. These movements emerge from necessity. They are inherently makeshift, electrically raw, and intensely personal.

The next phase arrives with a peculiar form of recognition. The mainstream cultural gaze shifts toward these subcultures, though this attention rarely stems from genuine understanding or solidarity. Instead, it is often a mixture of voyeuristic fascination and opportunistic appropriation. Designers proclaim themselves “inspired" by these gritty origins, lifting their most striking visual cues for high-gloss collections. Fashion editors anoint the aesthetic as “the next big thing" in glossy magazine spreads. The very same establishments that would have dismissed these styles as vulgar or threatening suddenly find them commercially desirable.

Vivienne Westwood, London

Inevitably, the machinery of commodification grinds into motion. The subversive statement is systematically repackaged as a consumable product. Its jagged edges are meticulously smoothed; its challenging message is diluted into something palatable for a broader, more conservative market. Consider punk's trajectory: a style born from raw anti-establishment fury now exists as a curated selection of pre-distressed denim and tastefully studded leather jackets in luxury boutiques. The queer aesthetics that once risked physical violence for those who wore them are sold back as ephemeral seasonal trends, frequently modelled by cisgender, heterosexual celebrities whose public image contradicts the very struggle that birthed the style. Even feminist slogan T-shirts, originally emblems of grassroots activism, are churned out by fast-fashion corporations notorious for exploiting female labour in their supply chains.

By the time a radical movement has been fully processed and absorbed into commercial fashion, it has been stripped of its transformative potential. The symbols persist as hollowed-out shells, their original meaning systematically evacuated. The rebellious silhouette remains, but its soul has been extracted. Thus, the cycle reaches its cynical conclusion: a style that once posed a fundamental challenge to the system is neatly repurposed, becoming just another product within that very system, its power to disrupt safely contained and converted into capital.

The Cost of Visibility: When Protest Becomes Palatable

The commodification of protest fashion extends beyond mere dilution of its radical potential, since it actively reshapes public perception of the movements themselves. Once a protest aesthetic migrates into the mainstream, it undergoes a dangerous transformation from a political statement into a performative accessory. Wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt no longer necessarily signals allegiance to anti-capitalist revolution; in countless instances, it merely indicates the wearer found the graphic composition agreeable. The Palestinian keffiyeh, a garment steeped in a long and painful history of resistance, is now frequently draped as a generic bohemian scarf, its profound symbolism ignored in favour of its textural appeal. Even the humble safety pin, briefly resurrected as a spontaneous emblem of solidarity following the Brexit referendum and Trump's election, rapidly devolved into a hollow token when disconnected from any substantive political action.

This transformation highlights the inherent cost of visibility within a commercial framework. The moment a protest aesthetic becomes fashionable, it simultaneously becomes safe. Fashion, in its current corporate incarnation, functions as an industry, and industries possess a fundamental aversion to causing genuine discomfort. For a movement to achieve commercial viability, its most challenging and disruptive elements must be systematically removed. The sharp, confrontational edge that once constituted its very power is carefully smoothed away; its original, complex meaning is sanitised and repackaged to ensure broad market appeal.

The result is a peculiar form of cultural neutralisation. The symbol remains visible, yet its capacity to provoke critical thought or inspire tangible action is greatly diminished. It becomes absorbed into the endless cycle of trends, where its primary function shifts from challenging power to complementing an outfit. In this sanitised state, the protest aesthetic no longer threatens the status quo; instead, it becomes a decorative, and ultimately complicit, part of the very system it was created to oppose.

Can Commercialisation Ever Be Beneficial?

Given this cycle of extraction and neutralisation, the relationship between commerce and cause seems irredeemably parasitic. Yet, to dismiss all commercial engagement as inherently corrupting may be to overlook more complex, if rare, possibilities.

Is commodification always function as a death sentence for a movement’s political integrity? Or can it occasionally serve a constructive purpose? The assumption that commodification inevitably neutralises fashion's political impact deserves closer scrutiny. In certain contexts, the mainstream adoption of an aesthetic can amplify a movement's message, carrying it to audiences far beyond its original reach. A mass-produced feminist slogan T-shirt may not single-handedly dismantle the patriarchy, yet if it prompts difficult conversations around office water coolers or funds grassroots organisations through charitable collaborations, it possesses a tangible, if limited, value. The Black Panther Party’s strategic use of coordinated, militaristic attire — the black berets and leather jackets — forged an unforgettable visual identity that commanded attention and projected disciplined solidarity. When contemporary brands like Pyer Moss dedicate entire collections to exploring Black history and systemic injustice, they engage in a form of commercialised resistance that, while operating within a capitalist framework, still forces important conversations into luxury retail spaces.

Similarly, the rise of gender-fluid fashion within luxury markets illustrates a complex tension between dilution and democratisation.There exists a genuine risk of erasing the courageous legacy of LGBTQ+ pioneers who wore ambiguous silhouettes when such expressions carried severe social and physical consequences. Yet simultaneously, seeing androgynous tailoring and fluid designs celebrated on prestigious runways and in global advertising campaigns actively challenges the deeply ingrained rigidity of gender norms within mainstream consciousness. The central question therefore becomes whether commercialisation can preserve the essential spirit of a movement, or if the process inherently renders its symbolism hollow.

One of the few scenarios where commercialisation might yield a net benefit occurs when it actively and transparently reinvests in the communities that originated the style. When brands establish genuine collaborations — involving shared creative direction, equitable profit-sharing, and long-term partnerships — with the artists and activists who pioneered an aesthetic, fashion can transform from an extractive industry into a potential force for economic and cultural empowerment. This model, however, remains the conspicuous exception in an industry still dominated by appropriation without attribution. The potential for benefit exists not in the act of commodification itself, but in the ethical structure and redistributive justice that can, on rare occasions, be built around it.

The Politics of the Runway: When Fashion Houses Take a Stand

Fashion is frequently dismissed as a frivolous enterprise, an industry preoccupied with surface over substance. Yet anyone who has truly observed a runway show understands its deeper potential. The catwalk has long functioned as an ideological battleground, a space where designers wage complex cultural wars using fabric and form, transforming clothing into a potent manifesto. Some sartorial statements are subtle, articulated through the inversion of a classic silhouette or a thoughtful reinterpretation of historical dress. Others are as direct and unambiguous as a placard at a political rally. In either mode, the political power inherent in the runway remains undeniable.

History provides compelling examples of collections that transcended mere aesthetic experimentation to become powerful cultural statements. Alexander McQueen’s Highland Rape (1995) served as a jarring, visceral commentary on England’s historical subjugation of Scotland. Models staggered down the runway adorned in torn lace and distressed tartans, their hair dishevelled and their expressions hollow. The show was intentionally shocking, a brutal reminder that fashion, when wielded with artistic courage, can unsettle audiences, provoke difficult conversations, and demand a reckoning with the past.

Rei Kawakubo’s Lumps and Bumps collection for Comme des Garçons (1997) presented a different form of radicalism. Through exaggerated, asymmetrical padding that deliberately distorted the female form, Kawakubo mounted a direct challenge to the rigid, classical ideals of beauty imposed upon women. The models appeared almost otherworldly, as though their bodies had actively rebelled against the tyranny of conventional symmetry. This was fashion operating as resistance, a rejection of the very expectation that a woman’s body should conform to any predetermined standard.

In more recent years, the political dimension of the runway has grown increasingly explicit. Under Maria Grazia Chiuri, Dior has consistently embraced feminism as a central theme, most notably with the “We Should All Be Feminists" T-shirts from her debut collection. The slogan, borrowed from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s seminal essay, effectively transformed a radical social critique into a luxury commodity. The move sparked considerable debate. Was this a genuine effort to amplify feminist discourse within a powerful cultural institution, or a performative gesture capitalising on the movement’s mainstream appeal? The answer likely hinges on whether one believes fashion possesses the capacity for meaningful political action, or merely reflects the politics of its time. Regardless, the very presence of such a discussion within the rarefied world of haute couture signalled a significant cultural shift.

Perhaps no contemporary designer has blurred the boundary between fashion and politics more deliberately than Demna at Balenciaga. His presentations are meticulously crafted dystopian spectacles that compel the audience to confront unsettling modern realities. His Winter 2022 show, staged within a vast, enveloping snow globe, became an unwitting symbol of global displacement and crisis, coinciding tragically with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Models trudged through artificial snow, swathed in heavy layers and clutching their coats as if fleeing an invisible threat, making it impossible to disentangle the collection from the grim context of current events. The effect was hauntingly effective, positioning fashion not as escapist fantasy but as a direct, uncomfortable confrontation with the world.

Even the Met Gala, fashion’s most opulent and exclusive gathering, has evolved into a platform for political messaging. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “Tax the Rich" gown in 2021, designed by Aurora James, perfectly encapsulated the inherent contradictions of fashion’s engagement with politics. Worn at an event teeming with the global elite, the dress ignited fierce debate. Was it a courageous act of defiance staged from within the belly of the beast, or a cynical, empty gesture that ultimately reinforced the very system it purported to critique? This paradox is central to fashion’s nature; it can simultaneously embody protest and privilege, rebellion and a tacit reinforcement of the structures it appears to challenge.

This duality constitutes the central tension of political fashion: the nebulous boundary where genuine resistance converges with commercial opportunism. A designer may create a collection that offers a searing critique of capitalism, yet those very pieces will be sold at astronomical prices, accessible only to a wealthy few. A slogan T-shirt may broadcast a revolutionary message, yet if it is produced under exploitative labour conditions, its ideological integrity collapses. The industry perpetually navigates this precarious line between subversion and complicity.

Despite these persistent contradictions, fashion’s power as a political statement endures. Its potency resides in its capacity to alter perceptions and force conversations into the public sphere, not necessarily in its ability to change policy directly. A single, courageous collection, or even a solitary, provocative garment, can disrupt entrenched expectations, generate profound discomfort, and challenge how people perceive their world. In this sense, the runway remains one of our most compelling stages for political discourse — a forum that communicates through the universal, visceral language of cloth, movement, and unforgettable spectacle.

Fashion’s Inescapable Capitalism: Can Brands Be True Allies?

This tension inevitably leads to a more fundamental question: can fashion brands ever function as genuine allies to activist causes, or will the inherent logic of capitalism inevitably corrupt their efforts? The answer remains deeply complex. The fashion industry is structurally and inextricably bound to a capitalist system that thrives on growth and, by its very nature, often involves exploitation. Consequently, even brands that outwardly champion progressive values frequently fall short of embodying them in their own operations. A luxury house sending a “We Should All Be Feminists" T-shirt down the runway while its supply chain relies on the underpaid labour of a predominantly female workforce. Reflect on a brand creating a powerful collection inspired by the plight of refugees, then pricing the garments at a level accessible only to the world's most affluent consumers. In such scenarios, the political statement risks becoming a hollow performance, a form of activism divorced from material action.

A handful of brands do attempt to integrate political alignment into their core identity with greater substance. Patagonia stands as a prominent example, dedicating significant resources to environmental activism and famously telling its customers not to buy its products unless absolutely necessary. Pyer Moss consistently uses its runway platform to spotlight erased chapters of Black history and celebrate Black cultural innovation. Even a house like Schiaparelli engages with fashion as a tool of surrealist disruption, challenging aesthetic and political conventions through its designs.

However, even the most conscientiously managed brands ultimately operate within a capitalist framework. This system’s foundational engine is consumption. For a brand to advocate for truly radical, systemic change would require it to challenge the very structures of overproduction and endless growth from which it derives its profit. The central, unresolved question therefore remains: how many brands possess the willingness to fundamentally dismantle the engine of their own existence? The chasm between making a statement and enacting structural reform is where most fashion activism ultimately falters, leaving the industry's role as a political ally perpetually ambiguous and fraught with contradiction.

Resistance Will Always Find New Threads

Yet, despite these structural limitations, the subversive potential of fashion remains undiminished. Clothing endures as one of the most democratic and accessible forms of protest, particularly for individuals who cannot safely participate in public demonstrations or vocalise dissent. A single garment can function as a quiet yet potent act of defiance, a method of signalling allegiance, solidarity, or resistance in environments where spoken opposition carries significant risk. This persistent power explains why authoritarian regimes and conservative institutions continue to police dress codes so rigorously, why specific garments face prohibition, and why authorities instinctively fear the symbolism of what people wear with an intensity matching their fear of spoken rebellion.

The commercial co-optation of radical fashion, while inevitable, never constitutes a final conclusion. The moment one movement is absorbed and neutralised by the mainstream, another emerges from the margins. The raw energy of punk may have been packaged and sold, but new underground subcultures continually rise to articulate fresh grievances. While certain queer aesthetics are commodified, the next generation devises innovative ways to challenge and expand the boundaries of gender and identity. The machinery of capitalism may be relentless in its consumption of dissent, but human creativity and the drive for self-expression possess an equal, if not greater, resilience.

Fashion will perpetually operate as a battleground where the forces of authenticity clash with those of appropriation, where the impulse for protest contends with the imperative of profit. Yet as long as structures of power exist, people will discover methods to contest them through what they wear. The true, enduring power of fashion as a political statement may reside in its limitless adaptability. While a specific sartorial protest might be co-opted, diluted, or rebranded, the fundamental practice of using clothing as resistance proves endlessly capable of reinvention.

Each generation cultivates its own sartorial lexicon of defiance, reclaiming symbols stripped of their original meaning and forging new ones that compel society to look again with fresh eyes. If the relationship between fashion and protest resembles a perpetual game of cat and mouse, then resistance consistently maintains its position one step ahead, constantly evolving its tactics and refusing to be permanently defined or subdued.

Ultimately, fashion transcends the mere selection of garments. It encompasses the intention behind how we wear them and the meaning we collectively ascribe to them. It is a fluid language that can be spoken in whispers or shouted from the rooftops, articulated through quiet, steadfast defiance or overt, spectacular rebellion. As long as power seeks to impose its will, fashion will continue to provide the threads with which to challenge it, stitch by deliberate stitch.

The Future of Fashion as Protest

As global instability intensifies, fashion's function within political discourse will only amplify. We are entering an era where one's clothing choices operate less as an expression of personal taste and more as a deliberate declaration of values. The realm of sustainability exemplifies this shift, having evolved into one of fashion's most contentious battlegrounds. The conscious decision to reject fast fashion, to embrace thrifting, or to champion ethical brands now constitutes a tangible act of protest, a daily sartorial vote against a destructive industrial complex.

Simultaneously, a significant danger emerges from fashion's accelerating commodification of activism. The troubling rise of “woke-washing" sees corporations adeptly capitalising on social movements while demonstrating little substantive commitment to their causes. A rainbow-coloured logo during Pride Month rings hollow if the company quietly funds politicians who oppose LGBTQ+ rights. A feminist slogan T-shirt loses all moral authority when stitched together in an exploitative sweatshop, its message directly contradicted by the conditions of its own creation. The distinction between authentic solidarity and cynical brand strategy grows increasingly difficult to discern.

Yet, despite this commercial co-optation, fashion will persist as one of our most visceral and immediate mediums for expressing conviction. Whether manifested in a student subtly altering their school uniform to challenge authority, a designer transforming the runway into a platform for political critique, or a global movement adopting a specific colour as its unifying emblem, clothing consistently transcends its utilitarian purpose. It functions as a language for the silenced, a weapon for the disenfranchised, a shield for the vulnerable, and a banner under which to march.

Ultimately, fashion has never been solely concerned with what we put on our bodies. It is fundamentally about the identity we project to the world and, more critically, the identities we consciously and courageously refuse to inhabit. In an age of escalating uncertainty, the way we dress remains a powerful, personal act of defining our allegiances and drawing our lines in the sand.

S xoxo

Written in Paris, France

23rd January 2025