Time, Spilled Like Champagne: Jonas Mekas and the Art of Forgetting to Remember

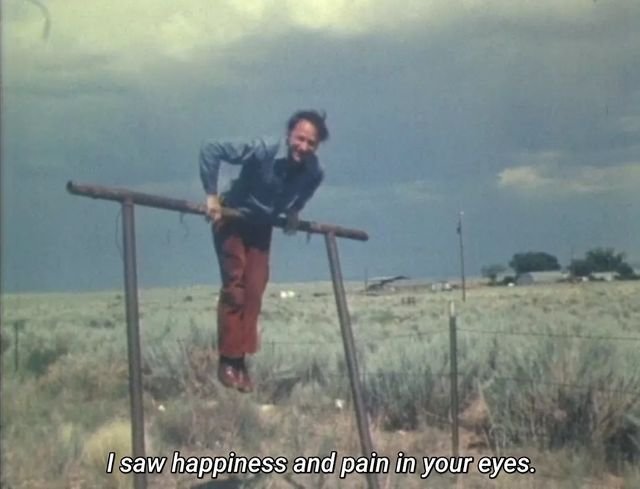

There is a scene, or rather, a flicker of one, in As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, where a child laughs, snow falls, and Mekas’ voice murmurs in that gentle Lithuanian lilt of his, as though he is speaking not to the audience, but to time itself. It is one of countless moments in the film, an ephemeral second caught and yet already dissolving. Watching Mekas is like watching champagne being poured — dizzying, joyful, spilling over before you can catch it. His approach to time is not linear but effervescent, bubbling and evaporating in real-time.

In a world obsessed with measuring, monetising, and maximising time, Mekas presents a radical alternative: time as sensation rather than schedule, time as poetry rather than product. This essay will explore how As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty rejects the capitalist obsession with efficiency and linear progression, offering instead a fragmented, intuitive relationship with memory and experience — one that embraces forgetting as much as remembering.

The Champagne Hour: Time as Emotion, Not Measurement

Traditional narratives function like well-planned business schedules. They have beginnings, middles, and ends, with clear resolutions and defined purposes. A novel follows a plot arc, a film has a three-act structure, even a song — at its most basic — moves from verse to chorus, building towards something, always heading somewhere. There is an expectation that time, too, must behave this way. That it must be linear, logical, productive. That it must take us from point A to point B with efficiency and purpose.

Jonas Mekas, however, refuses to treat time as something that should be structured or explained. As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty is, at first glance, a four-and-a-half-hour collection of home movies stitched together in a way that appears almost careless — scenes loop back, moments vanish before they fully materialise, time bends not according to chronology but according to feeling. One winter afternoon suddenly shifts to a summer morning decades earlier; laughter echoes across different years, different places. A woman turns her head, sunlight flickers across her cheek, and then we are somewhere else, somewhere entirely unrelated — except that, somehow, it is related. Not by logic, but by something deeper.

His editing style is the visual equivalent of half-remembered dreams, of trying to recall a childhood summer but only grasping the colour of the sky, the way the air smelled, the sound of distant laughter. Unlike the sharp precision of Hollywood storytelling, where each second is designed to advance a plot, Mekas lets images unfold with the randomness of memory itself. Snow falls on a city street, children run through fields, a cat blinks lazily in the afternoon sun. These are not moments chosen for their narrative significance; they are simply glimpses of life, recorded and then left to breathe.

And that, perhaps, is the most radical thing about his work.

For Mekas, time is not a straight road but a liquid thing — something that pools, spills, evaporates, only to rain down again in a different form. His approach to time is closer to how we actually live, how we experience memory. We do not walk through life with a constant awareness of narrative structure. We do not remember in neat, chronological order. We do not experience a moment and immediately file it away in a labelled folder, indexed by time and place. No — memories return unexpectedly, shaped by mood, triggered by scent, by music, by nothing at all. A chance encounter on the street may bring back the echo of a childhood voice; the way light filters through a window may feel like something from a decade ago. Mekas understands this. His films do not impose order on time — they let time exist as it does: shifting, unpredictable, fluid.

This is where he diverges most dramatically from the dominant view of time in contemporary life. We are told, constantly, that time must be managed, optimised, accounted for. That every hour must be made to count, that wasting time is a sin, that time is money. We measure our days in deadlines, in appointments, in productivity. Every moment must serve a function. But Mekas’ films reject this entirely. Here, time is not a currency to be spent efficiently — it is a feeling to be experienced. It does not accumulate into a grand meaning; it simply spills out, shimmering and dissolving.

To watch As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty is to step into a different rhythm of time — one that does not move forward but simply exists, unfolding moment by moment. It is the champagne hour, where time fizzes and sparkles, not rushing toward a conclusion but bubbling over, slipping between fingers, evaporating before it can be grasped.

This is not time as we are taught to understand it. This is time as it truly feels.

The Capitalist Clock: Time as Labour, Not Life

If Jonas Mekas treats time as something fluid and ungraspable, the modern world insists on treating it as something that must be controlled. Time is disciplined, measured, and above all, productive. We speak of time as though it is a dwindling resource, something that must be spent wisely, budgeted carefully, never wasted. We carve it up into work hours, lunch breaks, deadlines, and schedules. Time, under capitalism, is not something to be experienced — it is something to be used.

From the moment we wake up, time is already accounted for. The morning routine must be streamlined for efficiency; the workday is dictated by the relentless tick of the clock. Hours are tracked, logged, and exchanged for wages. Even leisure, once the ultimate escape from labour, has been absorbed into the capitalist machine, turned into a marketable industry where hobbies become side hustles, where relaxation must be optimised, where even doing nothing must somehow be productive. The world asks us, constantly, to prove that we are making good use of our time.

Mekas, however, asks no such thing. His films do not conform to the rigid logic of the workday. They do not attempt to be efficient, to compress life into neat, digestible arcs. His work unfolds in a different kind of time — one that stretches, breathes, meanders. Watching As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty is to experience time unshackled from purpose. There is no forward momentum, no grand structure leading to a final conclusion. Instead, there are fleeting moments: a street bathed in morning light, a woman laughing, a snowfall. These are not images designed to move a story forward; they are simply fragments of life, captured and allowed to exist without justification.

This refusal to organise time in a productive way is, in many ways, a quiet rebellion.

In a capitalist framework, time is transactional. It must be exchanged for something tangible — a salary, a product, a measurable outcome. Even in cinema, time is often treated with ruthless efficiency. Every second in a Hollywood film is engineered to serve a purpose: to advance the plot, to develop a character, to build towards resolution. Nothing is wasted. A shot that lingers too long, a moment that does not contribute to the story, is seen as indulgent, unnecessary.

Mekas, on the other hand, allows time to be extravagant. He lets it spill over, linger, take up space without explanation. His films do not seek to persuade, sell, or conclude. They are not concerned with progress, only presence. They remind us that not all time needs to be accounted for, that some moments can simply exist without being converted into something useful.

This is an increasingly radical idea. In a world where every moment is expected to contribute to some larger goal, the act of experiencing time for its own sake feels almost transgressive. To watch a Mekas film is to step outside of capitalist time, to reject the idea that every second must be justified. His work asks us to slow down, to embrace time not as a resource but as a sensation — something to be felt rather than measured.

And perhaps this is why his films can feel so disorienting to a modern audience. We are so accustomed to time being structured, monetised, turned into labour, that when confronted with time that simply exists — free, aimless, uncommodified — we struggle to make sense of it. Mekas’ work is a reminder that time does not have to be useful. That life, in its purest form, is not about efficiency, but about fleeting, shimmering moments.

In a world obsessed with productivity, there is something deeply liberating about that.

The Art of Forgetting: Memory as a Beautiful Failure

Jonas Mekas does not document life as much as he chases after it, knowing full well that it will always slip through his fingers. His camera is not a tool of preservation but of pursuit — an attempt to hold onto the ephemeral, to grasp at the ungraspable. And yet, no matter how much he records, something is always lost. There is a melancholic acceptance in his work, an understanding that memory is always incomplete, always failing, and that this failure is, in itself, beautiful.

Most autobiographies and historical documentaries attempt to build something whole. They shape the past into a structured, coherent narrative, filling in the blanks where memory falters, smoothing over the edges to create a story that makes sense. Mekas does the opposite. His films embrace the fragmentation of memory, the gaps, the distortions, the way certain moments linger vividly while others fade into obscurity. His work is not about preserving a definitive past but about evoking the experience of remembering itself — messy, scattered, nonlinear.

This aligns closely with Henri Bergson’s concept of duration (la durée), in which time is not a neatly ordered sequence but a subjective flow, shaped by perception rather than mechanical measurement. For Bergson, true time is felt, lived, experienced — something that cannot be captured in fixed, external structures. Mekas' approach to memory reflects this beautifully. His films are not timestamps; they are lived impressions, unfolding in a rhythm dictated not by chronology but by emotion. Each fleeting image is less about what happened and more about how it felt to be there.

Walter Benjamin’s reflections on memory and modernity also provide a useful lens through which to view Mekas' work. In his essay On the Concept of History, Benjamin contrasts two ways of understanding the past: the historicist’s linear, cause-and-effect sequence versus the more fragmented, associative experience of memory. He describes the flâneur — the wandering observer in the city — who gathers images and moments, not to build a singular history but to illuminate forgotten, peripheral experiences. Mekas, in his own way, is a flâneur of time itself, drifting through his own past, collecting fragments of beauty without concern for structure or resolution.

This is why watching As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty feels less like recalling a series of events and more like stumbling upon memories in real time. The film unfolds in bursts of sensation — sunlight flickering through trees, the sound of distant laughter, the warmth of a summer afternoon long gone. There is no logic to the sequence, no clear before or after. One moment dissolves into another, then another, as if we are drifting through someone else’s memories without a map.

And perhaps this is the only honest way to document a life.

Because memory does not work like an archive. It does not store experiences neatly in chronological order, ready to be retrieved at will. Instead, it is fluid, selective, shaped as much by forgetting as by remembering. Certain images remain vivid for reasons we cannot explain, while entire years blur into nothing. We remember not in facts but in feelings. The taste of childhood summers, the way a lover once looked in the half-light, the sound of a voice now lost to time. Our past is not a complete picture but a patchwork of scattered impressions. Mekas understands this. He does not fight against the unreliability of memory — he embraces it, makes it his subject.

In doing so, he turns forgetting into an art form.

His films are built not just on what is remembered but on the spaces in between, the absences that make memory what it is. The cuts, the flickers, the sudden shifts — they mirror the way we recall things in flashes, never quite in full. And yet, it is these gaps that make his work so deeply evocative. Because the essence of memory is not in its accuracy, but in its ability to conjure feeling. The past is not a collection of fixed facts, but something fluid, something that shimmers and shifts each time we reach for it.

Comparing Mekas to other filmmakers working within this space helps further illustrate his unique approach. Chris Marker, in Sans Soleil, similarly grapples with memory’s instability, presenting a filmic essay that drifts between time periods, places, and perspectives, questioning the very act of remembering. Agnes Varda, too, explores the fragility of recollection in The Beaches of Agnes, a deeply personal film that mixes documentary, self-portraiture, and poetic reconstruction to engage with her own past. Yet, while Marker’s film is intellectual and speculative, and Varda’s playfully self-aware, Mekas’ approach is even looser, more immediate. His films feel like memory itself — not a reflection on it, not an interpretation of it, but its raw, flickering presence.

To watch Mekas is to be reminded that the most precious things in life are often the ones we cannot fully hold onto. That the beauty of a moment is in its transience. That forgetting is not just a failure, but a necessary part of what makes memory so powerful. His films do not attempt to trap time — they let it slip through, leaving only traces behind.

And perhaps that is enough. Perhaps that is all memory ever is: brief glimpses of beauty, seen just before they disappear.

The Fleeting Now: Finding Beauty in the Momentary

Jonas Mekas’ philosophy is not nostalgic, despite being built on memory. Nostalgia often seeks to reclaim the past, to preserve it, to make it permanent. Mekas, however, embraces impermanence. His films do not long for what has been; they simply recognise it, honour it, and then let it go. In a world obsessed with documenting and archiving, where every moment is captured, posted, and stored indefinitely, Mekas portrays the value of fleetingness. His glimpses of beauty are not meant to be held onto — they are meant to be experienced and then surrendered.

To watch As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty is to be reminded that life is not meant to be neatly contained. It is something that spills over, fizzes out, disappears before you can catch it. Mekas’ work invites us to step outside the capitalist clock, to reject the idea that every second must be justified, and to embrace time as a sensation rather than a resource. His films are a quiet rebellion against the tyranny of productivity, a celebration of moments that exist for no other reason than to be felt.

In the end, Mekas does not offer answers or resolutions. Instead, he offers a way of seeing — a way of being. His films remind us that the most precious things in life are often the ones we cannot fully hold onto. That the beauty of a moment lies in its transience. That forgetting is not just a failure, but a necessary part of what makes memory so powerful. His work is a testament to the idea that life, in its purest form, is not about efficiency or accumulation, but about fleeting, shimmering moments that slip through our fingers like champagne.

And perhaps that is enough. Perhaps that is all memory ever is: brief glimpses of beauty, seen just before they disappear. In Mekas’ hands, these glimpses become a kind of poetry — a reminder that life’s most profound truths are not found in grand narratives or measurable outcomes, but in the quiet, ephemeral now. To watch Mekas is to learn how to live: not by chasing after time, but by letting it spill, fizz, and evaporate, leaving behind only the faintest traces of what once was, and the quiet promise of what might yet be.

S xoxo

Written at Marrakesh, Morocco

1st February 2025